The Gentle Art of Making Etchings

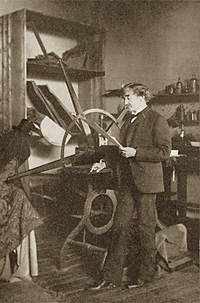

Whistler with his etching press in Paris

The Hunterian Art Gallery houses a world-famous collection of Whistler's prints and copper plates, which came to University of Glasgow as part of the artist's estate, augmented by later acquisitions. This exhibition marks year four of a five-year research project, led by the University, to produce an on-line catalogue raisonné of Whistler's etchings. The show focuses both on the discoveries and questions that have arisen during this research.

The Whistler Etchings Project explores Whistler's creative processes, through the development of his 500 etchings, from copper plate to finished print, providing a unique picture of a working artist. The choice of subject, composition and materials, in addition to the exhibition, publication and marketing of the etchings, is now being explored for the first time. So far over 9000 impressions of the etchings have been recorded in collections worldwide, from Hamburg to Honolulu.

The project is funded by the University of Glasgow, the Arts and Humanities Research Council, and private foundations. It enjoys collaboration with the Hunterian Art Gallery, the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, and the Art Institute of Chicago, with support from other institutions including Colby Art Gallery, Maine; the Library of Congress, Washington, DC; and the British Museum.

This on-line exhibition is based on a show at the Hunterian Art Gallery (January-30 May 2009), led by Professor Margaret MacDonald, Project Director, Whistler Etching Project, Department of Art History, University of Glasgow, with input from project staff Meg Hausberg, Chicago; Dr Grischka Petri, Bonn; Graeme Cannon (HATII), Dr Joanna Meacock and Sue Macallan, University of Glasgow; and by Professor Pamela Robertson and colleagues in the Hunterian Art Gallery.

ABBREVIATIONS:

GUW: The Correspondence of James McNeill Whistler, 1855-1903, edited by Margaret F. MacDonald, Patricia de Montfort and Nigel Thorp; including The Correspondence of Anna McNeill Whistler, 1855–1880, edited by Georgia Toutziari. On-line edition, University of Glasgow. http://www.whistler.arts.gla.ac.uk/correspondence

K: Edward G. Kennedy, The Etched Work of Whistler, New York, 1910

YMSM: Andrew McLaren Young, Margaret F. MacDonald, Robin Spencer and Hamish Miles, The Paintings of James McNeill Whistler, Yale University Press, London and New Haven, 1980.

HOW TO MAKE AN ETCHING

A thin copper plate was heated, covered with a thin acid-resistant ground, and smoked to produce a shiny black surface. Whistler drew with steel etching needles, which scratched bright copper lines through the ground. Etching is an intaglio process (from the Italian intagliare, 'to incise.') The incised lines were etched with nitric acid diluted with water, which bit down into the exposed lines.

After washing the plate, Whistler checked for scratches and mistakes. Then he could heat the plate, hammer out mistakes, and start again, using 'stopping-out varnish' to protect satisfactory areas. He also worked in drypoint, drawing directly on the plate with a needle, which threw up a metal ridge or 'burr'. Additions and changes were made in etching or drypoint. Each change produced a new 'state' of the etching.

The plate was cleaned, warmed, and dabbed with brown or black printer's ink. Surface ink was wiped off, leaving ink in the etched lines or drypoint burr. The plate, placed on damped paper, was pulled under pressure through the printing press.

The printed image appeared in reverse as fine dark lines. An indent (the plate mark), shows where the plate pressed into the paper. The first prints from a plate are often called proofs; all prints are known as impressions. A set of etchings, limited in number, could be published as an edition, by artist or dealer.

When enough impressions had been pulled from a plate, it was cancelled by drypoint lines or acid, and some impressions printed to prove that it had been cancelled. In a very few cases the plate was later restored and reprinted by other printers.

WHISTLER'S TECHNIQUE

Whistler soon moved beyond the technical training he received while working on the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey. He recognised that irregular patches and areas of small flecks, caused by accidents in biting his plates ('foul biting'), created tonal passages that added texture and variety to his etchings.

He learned that careful wiping or manipulation of ink could enhance etched lines ('retroussage') and the open spaces around them ('plate tone'). Later, in his masterful etchings of Venice, he built upon his early lessons in inking to achieve a perfect synthesis of line and tone.

Furthermore, from using drypoint touches to complete his etched compositions he moved to executing plates in the drypoint medium alone. While pure drypoints are in the minority among his intaglio work, Whistler employed the medium throughout his career to develop, refine or heighten the drama of his images.

He also achieved various effects by his choice of printing paper. He often printed proofs on heavy weight wove paper, and later impressions either on thin, glossy asian papers, or hand-made laid papers (laid lines show where the paper was dried on a ladder-like grid) with distinctive papermakers' watermarks, such as 'DE ERVEN Dk BLAUW' or the Arms of Amsterdam.

PRINTS, PROOFS AND PUBLICATION

The printed image appears as fine brown or black lines on the paper. A slight indent (the 'plate mark') appears round the edge, where the copper plate pressed into the paper. The scene appears in reverse on the paper. Since Whistler usually drew on site, from nature, his views are reversed. He had to write his signature back to front on the plate for it to be readable.

The first prints pulled from a plate are called proofs. Each print is known as an impression; and a defined number of impressions may be printed from any plate, 100 for Whistler's 'First Venice Set' and 30 for the 'Second Venice Set'. A set of etchings may be published as an edition, by the artist or by a dealer. They would usually be mounted and sold in an album.

A Series of Sixteen Etchings of Scenes on the Thames (the 'Thames Set', published in 1871), was presented in blue paper covers, while the 'Second Venice Set', published in 1886, was mounted, signed by the artist with his butterfly monogram (taken from his initials, JW) and presented in a brown paper album tied with yellow ribbons.

SALES AND STORIES

The history, context and subjects of Whistler's etchings repay close examination. His titles provide clues as to the subject, but these were often clearer to a Victorian connoisseur than to 21st century viewers. The Etching Project checks each etching, identifying models and sites, history and fashion, the symbols and stories that underlie his compositions.

The etchings can be mined for all sorts of information. Whistler did not always date the copper plate, but the form of his butterfly signature helps to date the printing of particular impressions. Dealers' stock numbers on the back ('verso') can be followed up in their ledgers. The mark stamped by a collector (usually a monogram), can be checked against catalogues and sales of their collections.

Whistler was influenced by the art market as well as influencing contemporary taste. Patterns of collecting emerge, with, for instance, some of the rare, delicate drypoints being of particular appeal to connoisseurs, and therefore fetching higher prices. Glasgow collectors like B. B. MacGeorge were among the first to collect Whistler's works, and when they died, their collections were dispersed among other major collections. Reconstructing the history of these early collections is a rewarding aspect of current research.

VENICE

In 1879 the Fine Art Society, London dealers, commissioned a set of etchings, which was published in an edition of 100 as Venice, a Series of Twelve Etchings (the 'First Venice Set') in 1880. Messrs Dowdeswell and Thibadeau published a further series, A Set of Twenty-six Etchings, in an edition of 30 in 1886. Whistler considered his Venetian work 'far more delicate in execution, more beautiful in subject and more important in interest than any of the old [Thames] set.'

Commercially Whistler's etchings did increasingly well. The early 'French Set' sold at 2 guineas (£2.2.0) for the set, with higher prices for the 'Thames Set'. In the 1870s he could ask 10 guineas for his best prints, while some of the Venice etchings were sold directly to collectors, bypassing the dealers, for as much as 15 guineas.

Both 'Venice Sets' included a variety of subjects, figures and views, most of which have now been identified. The skilful draughtsmanship, bold compositions and atmospheric use of printer's ink established Whistler's position as a printmaker and boosted his reputation among connoisseurs.

THE NAVAL REVIEW

The Naval Review celebrating Queen Victoria's 50th Jubilee was held on 23 July 1887.1. According to the Times, it included 'war vessels of all types and sizes… [a] spectacle of unparalleled significance and beauty'.2.

As President of the Society of British Artists, Whistler attended, carrying a pocketful of copper plates from Hughes & Kimber of London. During a long day at sea he produced several pencil sketches, a set of 12 etchings, and a watercolour.

Over the following weeks he etched and printed the small copper plates, keeping careful records, for once, of the process, in documents that form part of the extensive Whistler Collection given to the University by Rosalind Birnie Philip and now housed in Special Collections, Glasgow University Library.

SHOPS

Whistler searched the streets for subjects - children and chickens, shop-signs, posters in shop-windows.

He recorded a vanishing world, of local neighbourhoods and small, specialised shops. Whistler etched boot- and bonnet-shops; fish- and furniture-shops; fruiterers and greengrocers; print and picture shops; bird- and butchers' shops; sweet-shops and newspaper stalls; shops serving nuts, wine, and melons; fine jewellery shops and sordid rag-shops, from East-End London back streets, to Paris and the Latin quarter.

As compositions, shop-fronts fitted neatly on rectangular copper plates. Abstract, geometrical shapes underlie the human element of shoppers, and the decorative shapes of goods on display. These shops can often be identified from old postal directories, revealing a network of connections between Whistler and the people who lived and worked there.

AMSTERDAM

Whistler and his wife Beatrice visited Amsterdam in 1889. On 3 September he wrote to the Fine Art Society suggesting the publication of a set of etchings.

'I find myself doing far finer work than any that I have hitherto produced - and the subjects appeal to me most sympathetically - which is all important - … I have begun etchings here - that already give me great satisfaction - …The beauty & importance of these plates, you can only estimate from your knowledge of my care for my own reputation - … what I have already begun, is of far finer quality than all that has gone before - combining a minuteness of detail, always referred to with sadness by the Critics, who hark back to the Thames etchings, … with greater freedom and more beauty of execution than even the Venice set, or the last Renaissance lot can pretend to -'1.

Whistler suggested an edition of thirty, and a price of 2000 guineas. The Fine Art Society, still trying to persuade him to complete printing the 'First Venice Set', refused. However, Whistler and his wife printed and sold the Amsterdam etchings, which included some of his finest works.

THE RENAISSANCE SET

After their marriage in August 1888, James and Beatrice Whistler set off from Paris, travelling south through the Loire valley, calling at Bourges, Loches and Tours.

'So here we are - "in the Garden of France" - pottering about this old town in straw hats and white shoes!' Whistler told his sister-in-law '- sitting down on benches or borrowing chairs that we may, at our ease, look at the lovely old doorways - and marvel[l]ous carvings -'1.

Whistler's etchings from the trip, full of decorative Renaissance facades, sunny courtyards, and hidden châteaux, are rare and little known. Several are known only in the copper plates preserved in his studio and now in the Hunterian. Why they were not printed remains a mystery. Those that survive, drawn with summary nervous lines, in dots and dashes like shorthand, are notable for their delicate beauty.